From Pwn2Own 2021: A New Attack Surface on Microsoft Exchange - ProxyShell!

August 18, 2021 | Guest BloggerIn April 2021, Orange Tsai from DEVCORE Research Team demonstrated a remote code execution vulnerability in Microsoft Exchange during the Pwn2Own Vancouver 2021 contest. In doing so, he earned himself $200,000. Since then, he has disclosed several other bugs in Exchange and presented some of his findings at the recent Black Hat conference. Now that the bugs have been addressed by Microsoft, Orange has graciously provided this detailed write-up of the vulnerabilities he calls “ProxyShell”.

Hi, I am Orange Tsai from DEVCORE Research Team. In this article, I will introduce the exploit chain we demonstrated at the Pwn2Own 2021. It’s a pre-auth RCE on Microsoft Exchange Server and we named it ProxyShell! This article will provide additional details of the vulnerabilities. Regarding the architecture, and the new attack surface we uncovered, you can follow my talk on Black Hat USA and DEFCON or read the technical analysis in our blog.

ProxyShell consists of 3 vulnerabilities:

— CVE-2021-34473 - Pre-auth Path Confusion leads to ACL Bypass

— CVE-2021-34523 - Elevation of Privilege on Exchange PowerShell Backend

— CVE-2021-31207 - Post-auth Arbitrary-File-Write leads to RCE

With ProxyShell, an unauthenticated attacker can execute arbitrary commands on Microsoft Exchange Server through an exposed 443 port!

CVE-2021-34473 - Pre-auth Path Confusion

The first vulnerability of ProxyShell is similar to the SSRF in ProxyLogon. It too appears when the frontend (known as Client Access Services, or CAS) is calculating the backend URL. When a client HTTP request is categorized as an Explicit Logon Request, Exchange will normalize the request URL and remove the mailbox address part before routing the request to the backend.

Explicit Login is a special feature in Exchange to make a browser embed or display a specific user’s mailbox or calendar with a single URL. To accomplish this feature, this URL must be simple and include the mailbox address to be displayed. For example:

https://exchange/OWA/user@orange.local/Default.aspx

Through our research, we found that in certain handlers such as EwsAutodiscoverProxyRequestHandler, we can specify the mailbox address via the query string. Because Exchange doesn’t conduct sufficient checks on the mailbox address, we can erase a part of the URL via the query string during the URL normalization to access an arbitrary backend URL.

HttpProxy/EwsAutodiscoverProxyRequestHandler.cs

From the above code snippet, if the URL passes the check of IsAutodiscoverV2PreviewRequest, we can specify the Explicit Logon address via the Email parameter of the query string. It’s easy because this method just performs a simple validation of the URL suffix.

The Explicit Logon address will then be passed as an argument to method RemoveExplicitLogonFromUrlAbsoluteUri, and the method just uses Substring to erase the pattern we specified.

Here we designed the following URL to abuse the normalization process of Explicit Logon URL:

https://exchange/autodiscover/autodiscover.json?@foo.com/?&

Email=autodiscover/autodiscover.json%3f@foo.com

This faulty URL normalization lets us access an arbitrary backend URL while running as the Exchange Server machine account. Although this bug is not as powerful as the SSRF in ProxyLogon, and we could manipulate only the path part of the URL, it’s still powerful enough for us to conduct further attacks with arbitrary backend access.

CVE-2021-34523 - Exchange PowerShell Backend Elevation-of-Privilege

So far, we can access arbitrary backend URLs. The remaining part is post-exploitation. Due to the in-depth RBAC defense of Exchange (the ProtocolType in /Autodiscover is different from /Ecp), the unprivileged operation used in ProxyLogon which generates an ECP session is forbidden. So, we have to discover a new approach to exploit it. Here we focus on the feature called Exchange PowerShell Remoting!

Exchange PowerShell Remoting is a feature that lets users send mail, read mail, and even update the configuration from the command line. Exchange PowerShell Remoting is built upon WS-Management and implements numerous Cmdlets for automation. However, the authentication and authorization parts are still based on the original CAS architecture.

It should be noted that although we can access the backend of Exchange PowerShell, we still can’t interact with it correctly because there is no valid mailbox for the User NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM. We also can’t inject the X-CommonAccessToken header to forge our identity to impersonate a different user.

So what can we do? We thoroughly examined the implementation of the Exchange PowerShell backend and found an interesting piece of code that can be used to specify the user identity via the URL.

Configuration\RemotePowershellBackendCmdletProxyModule.cs

From the code snippet, when the PowerShell backend can’t find the X-CommonAccessToken header in the current request, it will try to deserialize and restore the user identity from the parameter X-Rps-CAT of the query string. It looks like the code snippet is designed for internal Exchange PowerShell intercommunication. However, because we can access the backend directly and specify an arbitrary value in X-Rps-CAT, we have the ability to impersonate any user. We leverage this to “downgrade” ourselves from the SYSTEM account, which has no mailbox, to Exchange Admin.

And now we can execute arbitrary Exchange PowerShell commands as Exchange Admin!

CVE-2021-31207 - Post-auth Arbitrary-File-Write

The last part of the exploit chain is to find a post-auth RCE technique using Exchange PowerShell commands. It’s not difficult because we are the admin and there are hundreds of commands that could be leveraged. Here we found the command New-MailboxExportRequest, which exports a user’s mailbox to a specified path.

New-MailboxExportRequest -Mailbox orange@orange.local -FilePath

\\127.0.0.1\C$\path\to\shell.aspx

This command is useful to us, since it lets us create a file at an arbitrary path. To make things better, the exported file is a mailbox that stores the user’s mails, so we can deliver our malicious payload through SMTP. But the only problem is - it seems like the mail content is not stored in plaintext format because we can’t find our payload in the exported file :(

We found the output is in Outlook Personal Folders (PST) format. By reading the official documentation from Microsoft, we learned that the PST just uses a simple Permutative Encoding (NDB_CRYPT_PERMUTE) to encode our payload. So we can encode the payload before sending it out, and when the server tries to save and encode our payload, it turns it into the original malicious code.

The Exploit

Let’s chain everything together!

Step 1 - Malicious payload delivery

We first deliver our encoded web shell to the targeted mailbox through SMTP. If the target mail server doesn’t support sending mail from an unauthorized user, Gmail can be also used as an alternative way to deliver the malicious payload externally.

Step 2 - PowerShell session establishment

Because PowerShell is based on the WinRM protocol, and it’s not easy to implement a universal WinRM client, we use a proxy server to hijack the PowerShell connection and modify the traffic. We first rewrite the URL to the path of EwsAutodiscoverProxyRequestHandler, which will trigger the path confusion bug and let us access the PowerShell backend. Then we insert the parameter X-Rps-CAT into the query string to impersonate any user. Here we specify the SID of Exchange Admin to become the admin!

Step 3 - Malicious PowerShell command execution

In the established PowerShell session, we execute the following PowerShell commands:

New-ManagementRoleAssignmentto grant ourselves the Mailbox Import Export roleNew-MailboxExportRequestto export the mailbox containing our malicious payload towebroot, to act as our web shell

Additional notes

After ProxyLogon, Windows Defender started blocking dangerous behaviors under the webroot of Exchange Server. To spawn a shell at Pwn2Own successfully, we spent a little time bypassing Defender. We found that Defender blocks us if we call cmd.exe directly. However, if we first copy cmd.exe to a <random>.exe under webroot via Scripting.FileSystemObject and then execute it, it works and Defender is silent :P

The other side note is that if the organization is using the Exchange Server cluster, sometimes an InvalidShellID exception occurs. The reason for this problem is that you are dealing with a load balancer, so a bit of luck is needed. Try to catch the exception and send the request again to solve that ;)

The last step is to enjoy your shell! Here is a demonstration video:

The Patch

Microsoft fixed all 3 of the ProxyShell vulnerabilities via patches released in April and May, but it announced the patches and assigned the CVEs three months after. The reason Microsoft gave is that:

Regarding the patch of CVE-2021-31207, Microsoft didn’t fix the arbitrary file write but used a allowlist to limit the file extension to .pst, .eml, or .ost.

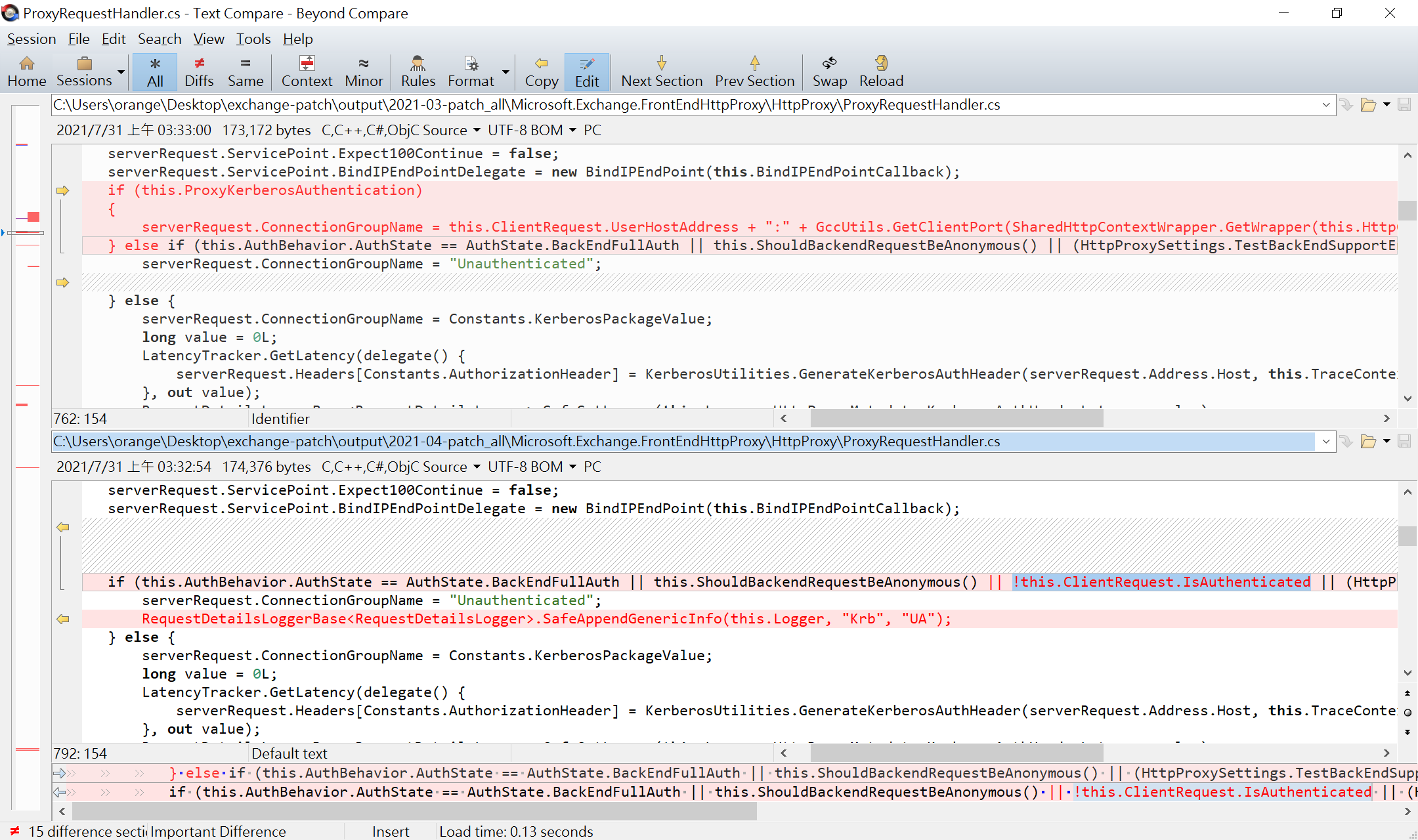

As for the vulnerabilities which were patched in April but assigned CVEs in July, Exchange now checks the value of IsAuthenticated to ensure all frontend requests are authenticated before generating the Kerberos ticket to access the backend.

Conclusion

Although the April patch mitigated the authentication part of this new attack surface, the CAS is still a good place for security researchers to hunt for bugs. In fact, we have uncovered a few additional bugs after the April patch. In conclusion, Exchange Server is a treasure waiting for you to find bugs. As we mentioned in our previous article, even in 2020, a hard-coded cryptography key could still be found in Exchange Server. I can assure you that Microsoft will fix more Exchange vulnerabilities in the future.

For the system administrators, since it’s an architecture problem, it’s hard to mitigate the attack surface with one single action. All you can do is keep your Exchange Server up-to-date and limit its external Internet exposure. At the very least, please apply the April Cumulative Update to prevent most of these pre-auth bugs!

Thanks again to Orange for providing this detailed analysis of his research. He has contributed many bugs to the ZDI program over the last couple of years, and we certainly hope to see more submissions from him in the future. Until then, follow the team for the latest in exploit techniques and security patches.